Last Friday, Facebook apologized to a grieving father for posting a “Year in Review” on his feed that featured his dead daughter.

Facebook’s “Year on Review” on my brother’s feed.

On Saturday, they posted this photo on my brother’s feed:

It’s a photo of our sister, Gabriela, agonizing on her death bed. She died later that day.

Gabriela got sick when she was 9 months old. She got síndrome urémico hemolítico (hemolytic-uremic syndrome– HUS). I was almost four when this happened and I don’t remember ever not knowing those words. I didn’t know their meaning, of course, because at the time nobody did. A syndrome, I was told, is a set of symptoms that go together without a known cause. Now we know that HUS is most often caused by e-coli or another bacterial infection. Not that it mattered, what mattered was that Gabriela got sick.

Gabriela got sick when she was 9 months old. She got síndrome urémico hemolítico (hemolytic-uremic syndrome– HUS). I was almost four when this happened and I don’t remember ever not knowing those words. I didn’t know their meaning, of course, because at the time nobody did. A syndrome, I was told, is a set of symptoms that go together without a known cause. Now we know that HUS is most often caused by e-coli or another bacterial infection. Not that it mattered, what mattered was that Gabriela got sick.

Ironically enough, I have rather good memories of the three months I spent living with aunt Gladys and Granny while Gabriela was at the hospital. My aunt and grandmother doted on me, and I enjoyed the visits to the hospital. The old, immense Hospital de Niños building was located in front of the Parque Saavedra, a huge park with a lake and plenty of green space. Later, in fifth grade, I would come back here with my class to do a “study” of its ecosystem. After every visit my aunt would buy me an ice cream bar. Back then children were mostly put in large wards. It was probably for that reason that, upon noticing that Gabriela was sick, my parents had taken her to the private Clínica del Niño. The doctors there didn’t know what to do with her. I’ve heard the story thousands of times: they kept filling her with serum while she couldn’t urinate until my father, worried, picked her up and took her against medical advice and without having her discharged, absconding with her to the public Hospital de Niños, where they saved her life. HUS, you see, is a disease of poor children, the Clínica doctors hadn’t seen it before. It was rare and worrisome enough, however, that my mother and Gabriela got the only single private room in the hospital. Some years later, it’d be occupied by my cousin Fernando. Those memories are not in the least bittersweet.

I still remember, as well, the names of the doctors who saved her life back then and kept her alive afterwards: Silver and Rentería. Their names would be replaced by others a few years later. While Gabriela survived HUS, her kidneys were permanently damaged. By the age of six, they were giving out on her.

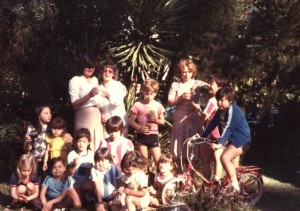

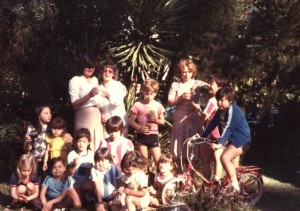

The three of us celebrating a doll’s birthday, c. 1978?

The CEMIC. The Center for Medical Education and Clinical Investigations in the posh Palermo Chico neighborhood of Buenos Aires. It became Gabriela’s home-away-from-home from the moment my parents found out about the possibility of a kidney transplant. There were so many tests; my father had a different blood type; my brother and I were too young; my mother’s kidney was not fully compatible. A German drug could work, perhaps, to bring down her immune system and prevent it from rejecting the kidney. Working with the insurance companies to get them to import it and pay for it. Getting Gabriela to gain weight so she could withstand the operation; getting my mother to lose weight to make it easier to take out her kidney. My vacaciones the invierno, winter break, that year were spent in a nice apartment close to the calle Florida, in Buenos Aires. It was owned by tío Héctor, one of my father’s college friends. Mamá and Gabriela were in the hospital, papá working and visiting them, I was pretty much on my own. I strolled the calle Florida, browsed at the toy stores and Harrods, ate the delicious pear jam that tío Héctor’s cousin was working to distribute. I visited Gabriela at the hospital some times. She was in an isolation room, all by herself. To enter, you had to cover your clothing, your head, your face and even your shoes. You had to wash your hands with disinfectant and then put on gloves. After her death, I discovered a letter I wrote to her while she was in the hospital, telling her about some little dolls I’d bought, advising her to be good to the doctors and nurses.

We celebrated Gabriela’s first transplant with an asado for doctors, patients and family members. 1979.

The rest, well, the rest is history. She got the transplant, a year later she started to reject it, two years later we had come to the US in search of a second kidney. It would take a year, two at the most, and we’d be back home. That’s what we thought. Instead, it was six, and I was a sophomore in college by the time it came. Before and after, well, there were health problems after health problems. My freshman year in college I wrote a poem about her death, I don’t even remember what particular health crisis she was growing through then. Peritonitis, convulsions, infections, my mom actually kept count of the hospitalizations, she’ll probably comment and say how many they were. My mom was with her on every single one. Every medical crisis presaged her death, but she didn’t die. Then she lost her second transplanted kidney, around the time I was having my second child; she refused to go back on hemodialysis so we waited for her to die. At the last minute, when the toxins in her brain were giving her painful hallucinations she consented to be treated, and there she went on until she had her third transplant, this time from a girl she met on the internet. The Wall Street Journal even wrote about that (years later, my husband would also be featured on a WSJ front page story, on a completely different topic).

Throughout my life I have made my peace with Gabriela’s death so many times that when it finally happened, it came as an enormous surprise. Truth be told, I believed she would outlive us all. She gave proof to the adage that death comes like a thief in the night, when you least expect it.

My relationship with Gabriela had deteriorated over the years. I loved her, I hope she knew that, but we clashed too much. I won’t speak ill of the dead because it serves no purpose, so let’s just say we did not get along. In part I was happy to say my last words to her after she died so she couldn’t talk back. But I think she knew what I would tell her: that I always loved her with all my heart, that I had given her as much of me as I could give her and still remain a person, that I lived every day with the guilty of the unfairness and senselessness that she had been sick and I hadn’t been, that she didn’t get to live a full life, and I did. As she laid dead, I spoke those words for myself, of course, but I also spoke them for her.

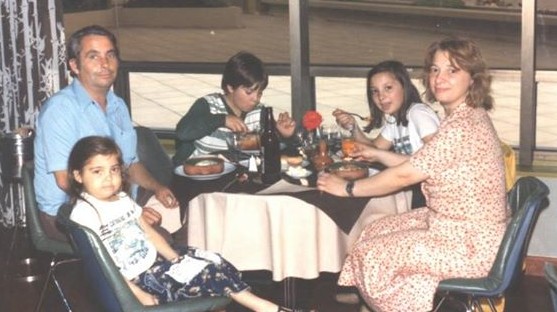

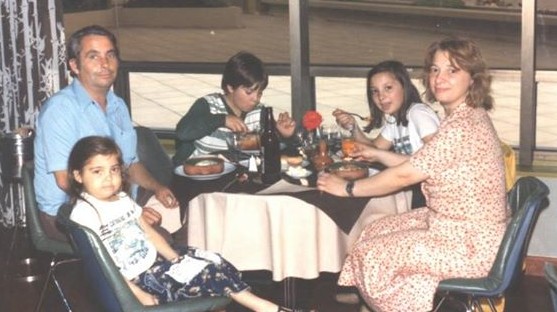

My family back in 1980, Gabriela is at the front.

But don’t get me wrong, while Gabriela and I were not close anymore, it’s in relative terms. There is a closeness in my family which I think is very unlike what I see in others, for better or worse. When we were young and my brother and I would express jealousy about how much more attention my parents paid to Gabriela than to us, my mom would say that her children were like her fingers. When one was injured, that’s the one she paid attention to, but the others were just as important and loved. I think that the five + 1 of us (Kathy, my younger sister, was born two years before I left for college) are like fingers. Too much part of a one to be individuals by ourselves. I don’t think I can grieve for Gabriela without grieving for myself, for my brother or for my parents.

And thus we go back to Facebook’s ill-timed photo. It didn’t appear on my feed, and for that I’m thankful, but it did appear on my brother’s. I understand why it did. I come from a large family, with tons of aunts and uncles and cousins and second and third cousins. Gabriela’s death was shared by everyone who lived her struggles. They couldn’t be there in person, so they were virtually around her. So they liked the photo, they commented on it, it was significant. Which does not mean that seeing it again was welcomed.

My biggest issue was not that this photo was posted by facebook on my brother’s feed, he can deal with his own traumas, but that it was posted adorned with bright colored circles and squiggles that look balloons and garlands. It’s a design that celebrates, that shows joy… at my sister’s agony and death. How incredibly crass is that? How cruel?

It’s bad enough that they did it, but it’s worse that they did it with full knowledge of the pain this could cause. After all, just like Friday they apologized for doing pretty much the same thing. When you apologize for doing something wrong, you are supposed to change your behavior, not do it again and this time with happier designs!

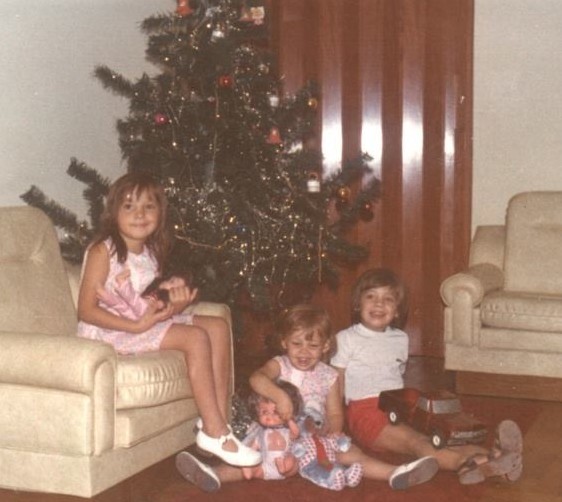

Some good has come of this, for me. I had been avoiding thinking about Gabriela this whole Xmas season, I didn’t want to break down and cry and I

have now done so, repeatedly, as I composed this post. I didn’t want to think about the fact that next year, when my whole family comes to my house for Christmas, she won’t be with them, I didn’t want to think about how there is a finger missing from that hand now and it will never be reattached, but I know I did both of us a disservice by avoiding thinking about her. I’m glad this forced me to and I can say Merry Christmas to the memory of that little girl that Gabriela was once upon a time.

Feliz Navidad, Gabriela!

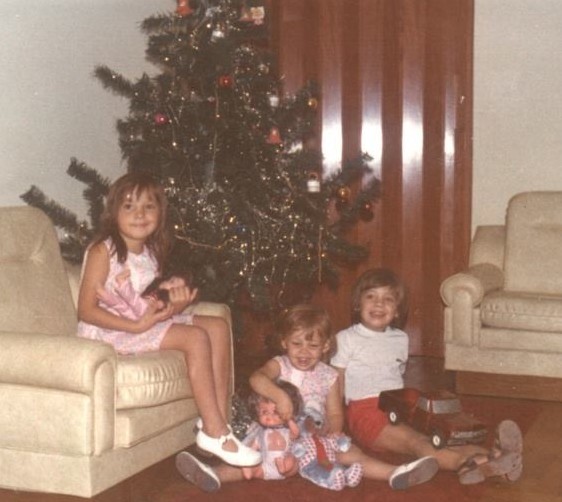

Christmas 1975?

Recent Comments