Granny and Gladys, my grandmother and my aunt, were probably the most important people in my life growing up – and both remained so until their deaths.

Granny and Gladys, my grandmother and my aunt, were probably the most important people in my life growing up – and both remained so until their deaths.

Granny, my father’s mother, had been born in 1893 – she was 76 when I was born. She was American, her father being a German immigrant and her mother also of German extraction. The story was that my great-grandfather, whose name escapes me, came to America to escape military service in Germany. Once upon a time I knew where he was from, but have since forgotten – as so many other stories my grandmother told me. The only one I seem to remember was of a dinner when she refused to eat her carrots and was made to sit at the table until she ate them. Apparently she did, which showed a lack of determination, I always thought.

She had been born in Albany, but had grown up as one of 8 children in Schenectedy, NY. I never thought of asking what her father did that allowed him to raise such a big family in what was described as quite a large house with a lot of land around it. Soon after Mike and I got married, he had a job in Boston and I flew to see him for a weekend. We drove all over New England, visited Schenectedy (what a dump!), looked for the house (which we might have found in a subdivision – surrounded by many other houses) and spent some time in the local cemetery looking for other Weisheits. I don’t think we found them. I wonder if my sister has found any of those second and third cousins – with 7 brothers and sisters, I’d imagine that there must be quite a lot of relatives out there.

Granny, on the right, with her sisters Gertrude (standing) and Grace Weisheit.

My grandmother worked in an office (could it have been at IBM?) and apparently my grandfather saw her across the street and decided he was going to marry her. Either that or he met her at church – which seems unlikely as my grandfather was Catholic and my grandmother was Lutheran. I’ve only seen one picture of my grandmother as a young woman (the one to the right) and I think she was quite striking – with curly blond hair (though she later had black hair, so that might have been an optical illusion in the cepia photograph), and big light-colored eyes. I’m hoping that someone in my family will sit down and record all the things I don’t remember. What was my grandfather, Ramón, doing in the US? He was in the Argentine Navy, and I have vague recollections that he was taking some kind of electronic course – I think he did electronics -, but in reality I have no clue. The point is that they met, they had what sounds like a brief romance, they married, and very soon my grandmother was in a ship to Argentina (what ship? The one that was bringing my grandfather back? How many questions that I never asked! – I should have undertaken this exercise while Gladys was still alive).

My grandmother was 20 at the time.

As it was expected and – given the lack of birth control – common at those times, she had her first son, Ricardo Kent, soon after she got married. Oh – Richard! That had been her father’s name, Richard Weisheit, for whom my uncle was named. Richard was also the name of her oldest brother. My impression has always been that she had been close to her brothers and sisters, all but one of whom died before I was born. The youngest one, at least a decade younger than my grandmother, was my aunt Grace. It was always clear to me that my grandmother held her in great affection, she actually came and visited Argentina before my grandmother died. Right before, if I well remember.

My grandmother, who doesn’t seem to have liked Argentina, Argentinians or Spanish a great deal, wanted to give her children English-sounding names. Alas, at that time – and until very recently – that was not an option. There was a list of approved names, all of which were in Spanish. Even if you immigrated, they translated your name into Spanish. Margaret became Margarita – and thus my own name.

She couldn’t name my uncle Richard, but after that brief homage to her father, he was to be known as “Kent” throughout his life – there is no Spanish version of Kent. My aunt would be Gladys – another name which is the same in Spanish – and my father would be David, which has the same spelling, but a different pronunciation, in English and Spanish. Indeed, my mother and family always called my dad “Davy” or “Deivi” – though I think his friends knew him as “Dah – VEEDH”.

My aunt Gladys was born 3 years after Kent (I think), but my father would only follow her 16 years later. He was the baby of the family – and I know that my aunt Gladys adored him. My uncle Kent got married very young and went on to have children only a few years younger than my father, so I don’t know that he was a major actor on my dad’s life. Kent was a purser in the merchant marine, but he was retired by the time I was born (or soon after). He was married to my aunt “Tota”, a High School classmate of Gladys, thus binding these two women together for life. I don’t think they liked each other much.

Gladys and Kent were also very close – had Tota not been around – I’d have described them as a matrimonio de hermanos, which is hard for me to translate, perhaps a “sibling marriage?” – this is a phrase that I’m borrowing from a story by Julio Cortazar to describe siblings that are so close that they are almost a couple. Perhaps that emotional closeness between Gladys and Kent is what caused so many problems with Tota. There is also the fact that my father and his siblings are all pretty calm, take-it-easy sort of people – but the women in their lives (my mother & Tota, at least) were quite the opposite. So am I.

When Gladys and Kent were children they spent some time in America – probably cementing their English skills. All of the children, including my father, were fluent in English – which makes me believe my grandmother always spoke English at home. Even after living over 60 years in Argentina, she spoke Spanish with a very heavy accent and did not fell comfortable in the language. It’s funny, the only accent I can “make” (as opposed to naturally have) is my grandmother’s American accent in Spanish. It’s quite amusing – and yet sad. I didn’t learn English as a child – despite those English language classes – and I wish my grandmother would have lived long enough for me to have been able to speak her cherished language to her. But perhaps it was better that way.

Even though my grandmother died when I was 9 years old (or was it 8?), I’m afraid that I don’t remember her that well. I remember our mutual love, but how was she as a person? Extremely patient, for one. I remember so many times, when I was very little, standing behind her on her favorite couch, “her” chair, playing with her hair, arranging it in whatever style I could think of. It must have been uncomfortable, even painful, not to mention the fact that she was careful about her hair. I won’t let my girls touch my hair. I guess that Granny loved me more 🙂

As I mentioned, my uncle Kent had children who were almost the age of my father. They were both boys, in their late twenties when I was born. Indeed, both of them had children older than I. So for my grandmother, it was a dream to have a little grand-daughter – her first. She really doted on me, not just with gifts and cakes, that was very measured in Argentina at the time, but with the type and amount of love that can only be felt. I loved my granny so very much and I cry now as I remember her.

What can I say about her? Gladys and Granny lived in an apartment several blocks from our apartment. They have moved there when the City Bell house where they had lived for years, became too big for them. I don’t remember if that was before or after my father got married.

Granny, and then Gladys, lived in that apartment until they died. It was a beautiful apartment, somewhat big and very comfortable. I lived there when I was three for three months – I’ll talk about that later – and later when I was fourteen for a year and a half. The last time I stayed there was after Gladys died. I had to strip it of most things in there, taking home some, giving away many more. So the apartment is not how I remember it any more. I don’t think I want to go back to it – and yet, it’s full of the essence of Gladys.

Gladys was 89 when she died – I’d seen her twice in the preceding six years, the last time, two years before she died. By then, she had started to look her age, though she had her hair died and styled until she died. But I don’t remember her at all that way. To me she looks like she did thirty-plus years earlier, when I lived with her. Her beautiful face, those aquamarine-colored eyes, lips always painted red, her hair short, blond and in curls. I remember her, though, with the red cardigan that I’d bought her. I gave it to her the last Christmas she spent here, in 2000, when actually my whole family came to our new home. I got her a cashmere cardigan, it was so soft. I completely forgot I’d given it to her, until I brought it home after she died – I couldn’t bare giving it away.

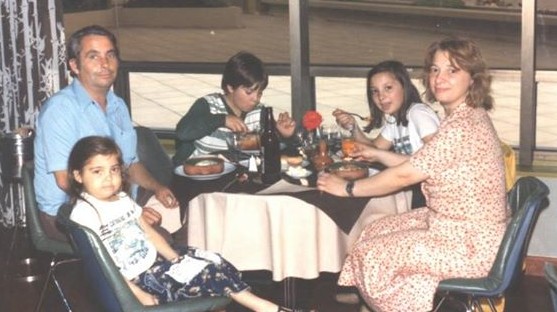

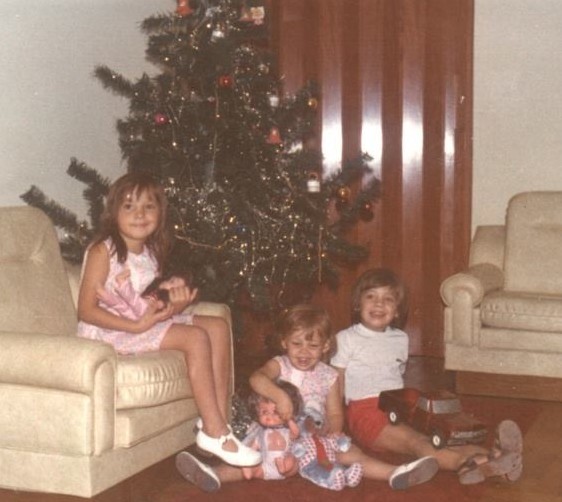

But let’s go back to my childhood, when Granny and Gladys were ever present. When I was almost four, on Three Kings Day 1973, my sister Gabriela, 9 months at the time, got sick, very sick. She got something called Hemolytic Uremic Syndrome, a poorly understood disease (not even a disease but a syndrome), that caused her a renal insufficiency. Basically, her kidneys stopped working. We know now that the syndrome is a consequence of oral exposure to e-coli, she must have eaten something bad. I don’t want to write now, and perhaps ever, of how her illness, the quest for a transplant which brought us to America, and everything that it involved, affected my life. It is too much and perhaps I still don’t understand it. My point here is just to tell that when Gabriela was sick, she was taken to the hospital where she spent three months. My mother stayed with her in that little room, open to a narrow patio. And for those three months, I stayed with Granny and Gladys.

Granny and Gladys, my grandmother and my aunt, were probably the most important people in my life growing up – and both remained so until their deaths.

Granny and Gladys, my grandmother and my aunt, were probably the most important people in my life growing up – and both remained so until their deaths.

Recent Comments