I’m not a storyteller.

Surprisingly enough, I didn’t realize that about myself until I was in my late thirties – when I had children who actually asked me to tell them stories. It’s almost tragic, I have none – I cannot make up stories nor can I relate stories from my life. It’s not that I don’t remember things, I just don’t remember any interesting things, or at least things that make stories. I do remember places, and people and occasions and feelings, but nothing that could fall into a narrative that would occupy more than a couple of minutes. My children so far haven’t noticed – they are used to board books that don’t have anything that could be called a plot -, but they soon will, and then mommy will be even more boring that she’s now.

My children want to hear stories of when I was a little girl, so I’ve been spending a lot of time thinking about my childhood, trying to remember anything that could even pass for a story. Instead, I immense myself in the places and times where I spent my childhood, one day visiting the casa quinta where I lived until I was 5, another day, warmly resting in the living room of my grandmother’s house. It’s been so many years since I’ve thought about these things, these times, and I always feel so warmly when I do. It’s as if all the sad memories have disappeared, and only the security of childhood remains. Am I giving my children the same sense of warmth that I feel looking back? Only time will tell.

And then, my other big question, will I forget these memories? I have forgotten so much. So many times I look at a picture of me and have no idea where or when it was taken. What was I doing? What was I feeling? All gone now. Now, eleven years later, I know that, indeed, I am forgetting a lot of details. Memories, when they are here, are far more fuzzy.

So I thought that I might want to record some of these memories for me, for the future, and perhaps even for my children. No doubt that they’ll be boring to read – as I said, I’m not a story teller – but perhaps one day I will enjoy them nonetheless. So I start now.

When I was one and two and three and four, not, I think, when I was five, I lived with my parents, and later my siblings, in a small house (that seemed so huge to me), somewhere in the outskirts of La Plata. I don’t know the address or the name of the locality – when people asked where we lived, the answer was always camino a Olmos – on the road to Olmos. I knew nothing about Olmos, though today the name is associated in my mind with a woman’s prison and with clandestine births. I had a vague feeling, one that I have not bother to confirm, that if you continued further down that road, you’d also arrive at Melchor Romero, a very large manicomio, or insane asylum. My mother had worked or at least visited Melchor Romero when she was studying social work in college. She had many gruesome stories of the people she had met there – the only one I can remember now was of a man who killed his little brother and ate him. Clearly, that story made an impact on my young mind.

The house where we lived belonged to my grandfather, Tito. It also belonged to my grandmother, Zuni, but I don’t think I ever saw her ethereal figure as that of someone who owned things. Things beside the high heel white pumps that I liked to wear or those thick wool skirts that smelled faintly of moth balls. Later, much later, she would buy a rabbit fur coat at the peletería, or fur store, that belonged to the father of my friend Karina (with whom, coincidentally, I have just reunited through facebook). The coat also smelled faintly of moth balls, but it was so soft to the touch. I can’t help but remember her small frame swimming in the mountains of gray fur. But as I said, that was later.

The house, as I was saying, was probably small. It had a large kitchen (or was it that large?), with a door and window opening to the patio criollo, that tiled (was it tiled?) rectangular patio where I’d first work at learning how to ride my blue bicycle (a gift from my grandmother “Granny” when I turned five). There was one bedroom occupied by my parents’ bed, our white crib and a large wardrobe. The house must have been old, built before built-in closets became standard. I don’t remember any furniture in the living room part of the living-comedor. Later, after my sister was born, when we were getting ready to move into the La Plata apartment, my mother bought a sillón-cama, a hide-a-bed sofa, where I slept. I’m sure I’ll write more about it. For now, let’s just say that it had an Italian style and was made of light-colored fake leather. A large table (I know it was large, because I’ve seen the pictures), perhaps a cupboard, that I remember very faintly.

There was another room, my father’s office. From there, I remember a metal desk lamp and a tall chest of drawers (which later would be cut into two and placed in the closet in my room, in the new apartment). My father was still studying engineering, so I think he may have had a draftman’s desk – I can’t remember it. He did have one of those adjustable table lamps with multiple articulations.

And then there was the bathroom. A toilet, a sink, a shower (or rather, a shower head in the middle of the bathroom). I think I remember, but it could be any bathroom.

There was another bathroom outside, beyond the patio criollo. It was the one used by Panchito, our next door neighbor. For some reason, the bathroom in his house didn’t work so he’d come to use ours. The one outside, of course.

I don’t remember much about Panchito, I may very well have stopped seeing him after we moved to the city, I can’t remember his face at all. I know that even then I thought he was off, but beyond the lack of a bathroom, I’m not sure why I felt that way. I should ask my mother if she remember him and can tell me more about him.

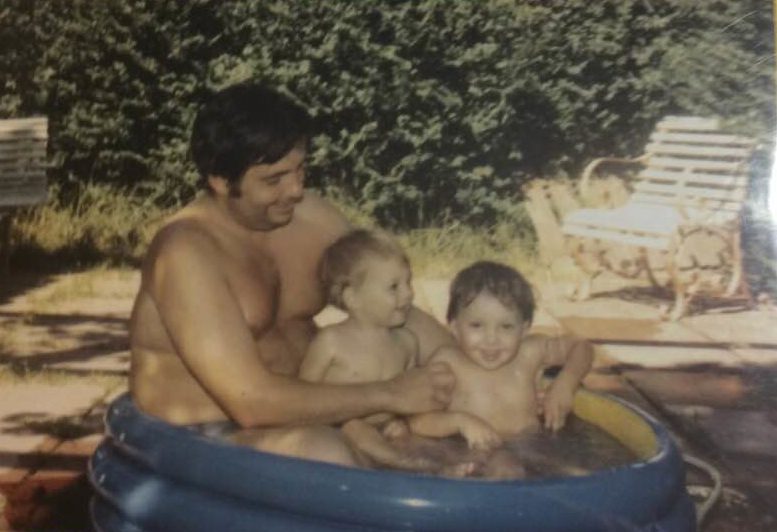

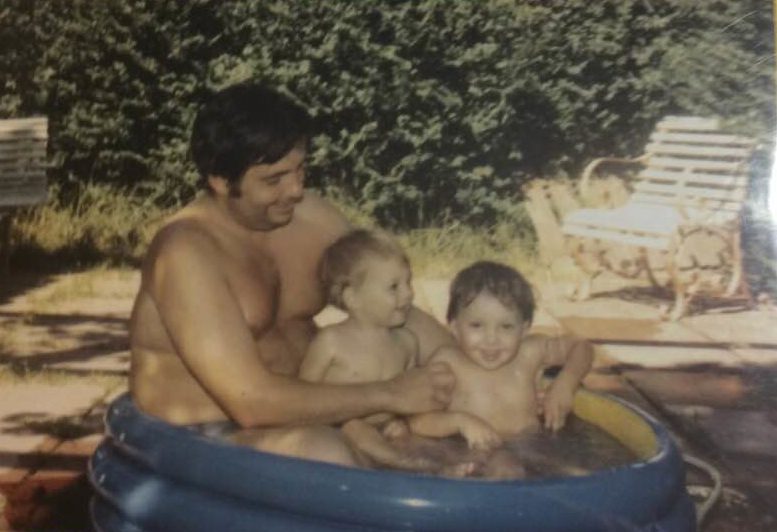

As little or as much as I remember, my parents seem to have forgotten. My dad at least. One of my fondest memories of those years was my father arriving home from work with small “Jack” chocolates. These minute chocolates came with a tiny plastic figurine, at that time of Titanes en el Ring, a wrestling ensemble that featured wrestlers dressed up as characters. The most popular and lethal of all was the “mummy”, that could put you down by just touching you. It didn’t show up that often, but when it did, we were wild with enthusiasm. The troupe had been created by Martín Karadagián, an actor and wrestler who sometimes would show up as well – when he did, he always won. A couple of decades later I virtually met his daughter in a mailing lists for Argentinians abroad.

In any case, once in a great while my father would bring us those chocolates when he came home from work. I still remember how he looked like, so young, so masculine, with dark black hair. He was very good looking, known, indeed, for his looks. But mostly, he was a very kind man, very loving, a nice dad (usually).

As sweet as the memory of the jacks is for me, my dad does not remember it at all. We went to Argentina a couple of years ago, when my aunt Gladys passed away, and I bought a bunch of Jacks for my girls (I’d introduced them to the chocolates during our last trip there) – so I told my dad about my fond memories. He had no idea what I was talking about.

The casa quinta had a name: Stella Maris. It was my youngest aunt’s name, given to her, and the house, by my mother. Still, we always referred to it as the quinta.

The house might (or might not) have been small, but it was in a large lot with lots of fun things for kids to explore. At the other side of the ligustro, which marked the end of the patio criollo, was a single (I’m pretty sure it was a single) swing. Nothing special, but then again, children like swings no matter how simple they are. In front of the swing was a kumquat tree. I haven’t eaten a kumquat in 35 years, but I can still remember their bitter taste. I didn’t particularly like them; my mother did.

Behind the other wall that bordered the patio were tall daisies (margaritas) and calla lilies. I haven’t seen such big daisies since. I liked them, mostly, because of my name. I still do. When my aunt Gladys was alive, I sent her a bouquet of daisies (usually with roses or other flowers) for her birthdays and mother’s day. When she died, I left a few of these humble flowers with her. But I can’t think of Gladys now – because when I do, I cry, and that’s not my intent here. Re-reading this eleven years later, when my time has taken even more of its toll on my memory, I stop to note that my father died two weeks ago and that my daughter, at my request, placed daisies in his casket.

At some point, but I think that was later, after we moved out and my uncle Aníbal (el Cabezón) moved in, there were also bee hives (the kind you raise). There must also have been trees, I only remember one where we found a caterpillar. Actually, I remember the caterpillar, not the tree. Silly me of eleven years ago, I remember the tree well. Tall (to me) and full of leaves. I was afraid of the caterpillars, they hurt when they touched you.

On the far back of the lot was the quincho with the parrilla; there we would have our asados. I can still picture my father’s wooden plate, what he used to transfer the meat from the parrilla to the table. Near there, there was the skull of a cow and further away, the place where we’d burn the trash (no garbage collection at the time, I guess). It was there where I hid (though there was nowhere to hide) the day my father gave me the greatest paliza, spanking, I ever got.

I have told this story many times – to my kids, who, for some reason, like to hear it over and over. And it goes like this…

One day, when I was a little girl, my father took me to the general store across the road (that road that went all the way to Olmos), to buy something I have well forgotten. I wanted chocolate (perhaps those same Jacks I talked about before, but I don’t quite remember). He wouldn’t buy them for me. I threw a fit and ran away, crossing that feared road (I did look both ways, and then ran across it) and heading towards my house. There I met with my mother and siblings (I had two, I must have been about 4); my mother warned me that I was in big trouble, and I knew it, of course. So I went hiding, and I guess there was no place to hide because I ended up by the area where we burnt the garbage. Perhaps by then I was resigned to the spanking – I learned, later, that the best way to deal with spankings was to accept them, the expectation being almost always worse than the actual punishment – but I stopped running. And my father found me, and he spanked me, and of that I remember nothing.

And this is it for tonight. I hope there will be more nights like this, me and my memories – but I’m not very consistent. So many times I’ve told myself that I wanted to keep a diary, and I’ve never gone more than a day or two with it. Oh well. Hopefully I’ll be back.

Recent Comments